This case involved a Nigerian crime ring that stole Apple computers and devices by impersonating U.S. defense officials. Make sure purchase orders pass the “smell test,” and call agencies to confirm.

I was the contract chief financial officer for a computer software and hardware reseller to government and government contractors. The case began one summer day with an email I received from the chief operating officer of the company, which I’ll call “NearWare.”

“Call me on my cellphone as soon as you get a chance,” the COO said. “The FBI just stopped by our office, and we have an urgent issue.” Now there’s a message that’ll get your heart racing. When I talked to the COO, it became clear that the group of military orders recently placed at NearWare for nearly $500,000 were fake.

The FBI described the fraud for us. A Nigerian crime ring would look online for contractors and then contact Apple and other manufacturers to get lists of their resellers for their products. Once they determined that a reseller sold to the government, they used their inside connections at military bases to order and arrange for receipt of orders —

via military-looking email addresses and live phone calls — which they would later sneak off the bases.

In this case, the fraudsters put together a convincing government purchase order and sent it to NearWare’s office. It even had the correct contact name, whom I’ll call “George Smith,” for the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA). NearWare called George, and though he spoke some broken English, in Washington, D.C., that wasn’t that unusual.

Because the DLA had ordered from NearWare in the past, it wasn’t that unusual to receive more orders. So, after NearWare did some cursory checking, it shipped the first Apple computers and iPads to a military base. Then more orders came in for different bases. Same story. Ultimately, the fraudsters paid about $3,000 for a small order, which further reduced risk around the account because it wasn’t showing as overdue. However, the orders eventually totaled $430,000. After NearWare talked with DLA accounting it realized it wasn’t going to be paid.

Examining the facts and piecing together the evidence

Even though the fraudsters used official-looking, spoofed “.mil” military email addresses, a closer look showed their true, non-government addresses. The damage had been done.

The fraudsters used at least two mules: one who made the deposit for an early shipment into a Maryland bank and another who worked at the DLA military barber shop who arranged shipments from the bases to a ship that was bound for Nigeria. They duped military shipping clerks and a shipping company into rerouting packages from military bases and the shipping company’s facilities to its offices. The fraudsters would walk into one of the shipping company’s offices, give tracking numbers, say they were George Smith and collect the packages addressed to George.

Neither the shipping company nor the DLA would take responsibility even when NearWare sued them, and they didn’t provide information because they obviously were also duped when they unwittingly hired criminals to work at their shipping docks and barber shops.

Reasons this fraud was successful

1.The customer, the DLA, already had an approved account with net 30-day terms in NearWare’s system.

2.George Smith was an actual employee at DLA.

3.The emails, phone calls and purchase-order documents seemed legitimate.

4.NearWare was shipping to military bases, and the addresses were actual military bases, which made this seem legitimate.

Identifying and prosecuting the fraudsters

On Feb. 3, 2017, BabatundeAniyi, of Lagos, Nigeria, was sentenced to 33 months in prison for a conspiracy to defraud U.S. defense contractors, including DLA, and impersonation of U.S. officers, according to a U.S. Department of Justice release.

Aniyi was also ordered to pay $1,515,524.18 in restitution to his victims, which also included the Missile Defense Agency, Defense Information Systems Agency and Defense Contract.

Audit Agency. (See Nigerian Man Pleads Guilty In $1.5 M DOD Contracting Scheme, by Matthew Perlman, Law360, Oct. 21, 2016.)

According to court documents, Aniyi and a co-conspirator in Nigeria, BabatundeOpeifa, impersonated U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) officials using fake DOD email accounts and websites. As the FBI had told us, Aniyi and his co-conspirator ordered computers and smartphones in the name of DOD officials and diverted the packages to Nigeria, with the help of two of the U.S.-based co-conspirators, Solomon Oyesanya and OludayoEdgal.

Oyesanya and Edgal pleaded guilty to conspiracy charges last year and were sentenced to 60 and 27 months in prison, respectively. According to court documents, the conspiracy caused more than $1.5 million in losses.

Aniyi was arrested in India in November 2015 while attending a course on computer hacking and was extradited to the U.S., according to the DOJ.

Spoofing details

Spammers spoof emails by sending them with forged “from” addresses. Many of the top website domains are failing to properly use authentication systems, which opens the door to spoofing, according to Sweden-based Detectify, a security firm. The company analyzed the top 500 websites ranked by Alexa and found that 276 of the domains are vulnerable, it reported in a blog post. (See Misconfigured email servers open the door to spoofed emails from top domains, June 20, 2016, Detectify.)

Of the vulnerable domains, 40 percent were news and media sites, and 16 percent were software-as-a-service sites, Detectify said.

These domains are trying to prevent email spoofing via a validation system called Sender Policy Framework or SPF, according to Detectify, which essentially creates public records and provides the internet with those email servers that are allowed to use the domains. Ideally, any messages impersonating the domains will be detected as spam and rejected before delivery.

In practice, however, the system often comes up short. The SPF will filter out spam emails best when on the so-called “hardfail” setting, but many website domains decide to implement the SPF at the “softfail” level because too many flagged emails interferes with workflow. Although the lower level will flag any forged emails as suspected spam, the messages still will be sent out to the recipients.

Companies in charge of website domains do this to avoid losing legitimate emails that might be falsely flagged, says John Levine, a long-time email infrastructure consultant in Top website domains are vulnerable to email spoofing, by Michael Kan, June 22, 2016, PCWorld from IDG News Service. “There are a lot of ways to send mail legitimately, and SPF can only describe some of them,” he added in the PCWorld article.

Email providers such as Gmail can also skip marking any messages as spam, even if an SPF system softfail was used, according to the Detectify blog.

The 276 web domains found vulnerable weren’t using any SPF system or had set their SPF system on softfail. Others had misconfigured their email validation systems to do nothing when detecting spam, Detectify said.

Companies in charge of these domains are either unaware of the problem or assume they’re already protected, Detectify said. Enacting better email validation systems can also be complicated, and some companies don’t see it as a priority, according to the PCWorld article.

NearWare implodes

The fraud left NearWare susceptible financially because it was still responsible for paying vendors. Margins in the business were small, so the company laid off employees and lost its financing. Former salespeople disregarded their non-compete agreements and set up shop at competitor companies. They bad-mouthed NearWare’s financial situation and profited. The company’s revenues withered down to almost nothing and had no employees.

Lessons for companies

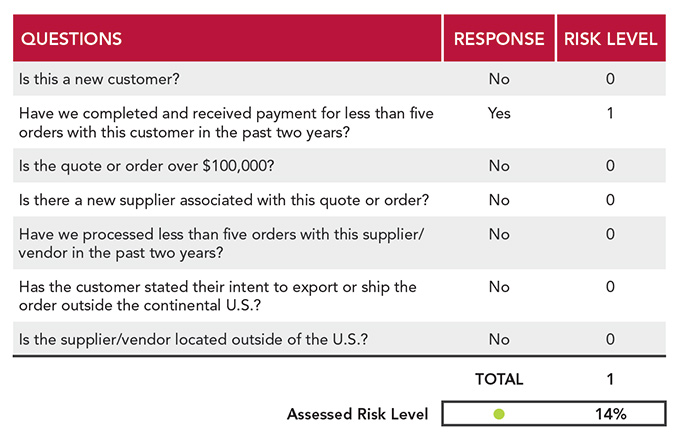

After the fraud, NearWare instituted a risk-assessment form (see figure below), which weighs such factors as a customer’s order size, dates of recent orders from this customer, destinations, etc. Unfortunately, it was too little, too late.

Organizations have to train employees to scrutinize email addresses to avoid spoofing. Advanced automatic email filters help, but sometimes legitimate emails can be suppressed.

The only sure way to detect fraud in customer orders is to call the customer. In this case, if NearWare had just called the real George Smith, he would’ve denied ever placing the orders, and NearWare wouldn’t have shipped anything.

Strong controls are imperative, but sometimes employees and executives have enough experienced skepticism to know when supposed vendors don’t pass the “smell test.” I know of another contractor that Aniyi almost defrauded if it wasn’t for a savvy salesperson and an astute, involved, hands-on CEO who felt “George Smith” was trying to unduly rush the deal. They canceled the orders just before they were shipped.

Fraudsters will always exist. They attend fraud conferences. They try to learn from us to keep one step ahead of technology and processes. The best we can do is keep fighting the fight and learning and educating others to prevent and deter fraud.

Bob Bates, CFE, CPA, is owner of HP Accounting Services Inc. in San Francisco. He wrote a shorter blog version of this column for his company’s website. Contact him at mail@hpaccounting.com.